- July was the hottest month ever on record. This summer, vast areas of the Arctic were engulfed in flames. Satellite images showed plumes of smoke engulfing parts of Russia, Greenland, and Alaska.

- These wildfires can be linked to the warmer temperatures and drier conditions that climate change brings.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

The Arctic is known for its icy expanses, frozen tundra, and massive floating glaciers. Not blazing wildfires.

But in the midst of a record-breaking summer, the Arctic is burning.

Last month, megafires razed the northernmost parts of Russia and Greenland.

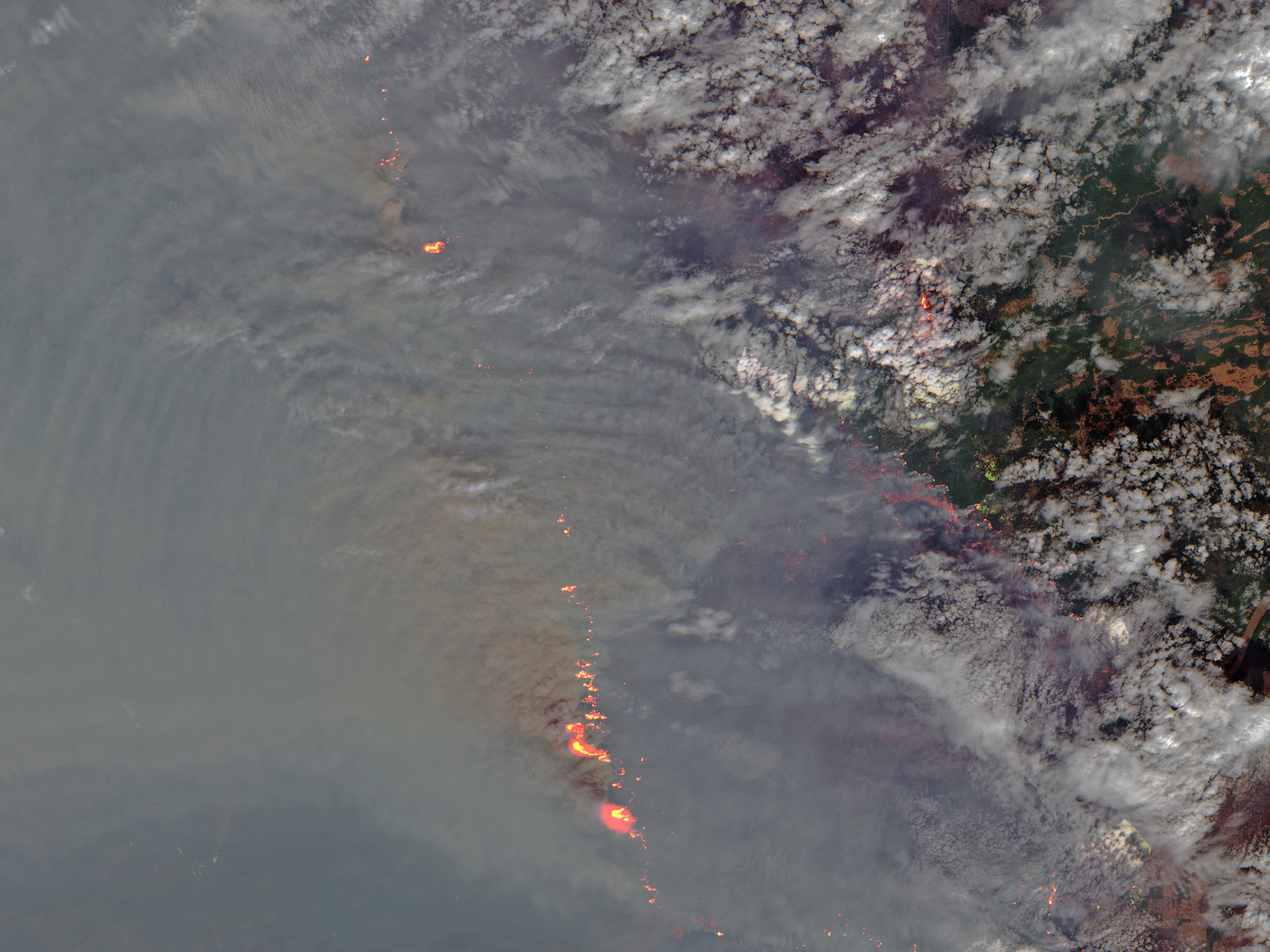

In Alaska, meanwhile, 2.4 million acres of forest have burned this year. In June and July, plumes from the Swan Lake fire (seen in the satellite image below) engulfed Anchorage. Amid the smoke on July 4, the city experienced its hottest day in recorded history: 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius).

These blazes were big enough to be seen from space: On July 24, colossal pillars of smoke were visible above Russia, Alaska, and Greenland simultaneously.

As of today, parts of British Columbia, Canada and Alaska are still burning, while more than 13.5 million acres of Siberia are ablaze.

The link between fires and climate change

Individual wildfires and heat waves can't be directly linked to climate change, but accelerated warming increases their likelihood, size, and frequency.

July was the hottest month ever recorded, period. The month prior, meanwhile, was the hottest June ever in Earth's history, with temperatures nearly 20 degrees Fahrenheit above average. Two heat waves hit Europe, killing dozens.

Overall, this year is on pace to be the third hottest on record globally, according to Climate Central. Last year was the fourth warmest, behind 2016 (the warmest), 2015, and 2017. Last year was also the hottest year on record for the world's oceans.

This warming can be linked to greenhouse-gas emissions. When heat-trapping gases like carbon and methane enter the atmosphere (they get emitted when we burn fossil fuels, among other human activities), they trap more of the sun's heat on the planet, causing Earth's overall surface temperatures to rise.

This graphic from NASA depicts the trend.

Hot and dry conditions in the Northern Hemisphere are a consequence of this unprecedented warming. That's because warming leads winter snow cover to melt earlier, and hotter air sucks away the moisture from trees and soil, leading to dryer land. Decreased rainfall also makes for parched forests that are prone to burning.

Combined, that has created ideal conditions for wildfires in the Arctic.

The European Union's Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service said its team has observed more than 100 intense and long-lasting fires in the Arctic Circle since the start of June.

"Climate change, with rising temperatures and shifts in precipitation patterns, is amplifying the risk of wildfires and prolonging the season," the World Meteorological Organization wrote.

Wildfires are more likely now - and also bigger

In the western US, the average wildfire season is 78 days longer than it was 50 years ago, likely due to climate change, the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions reported.

Fires are getting bigger, too. A recent study found that the portion of California that burns from wildfires every year has increased more than five-fold since 1972.

Twelve of the 15 biggest fires in the state's history have occurred since the year 2000.

Nationwide, large wildfires in the US now burn more than twice the area they did in 1970.

"No matter how hard we try, the fires are going to keep getting bigger, and the reason is really clear," climatologist Park Williams told Columbia University's Center for Climate and Life. "Climate is really running the show in terms of what burns."

What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic

Arctic wildfires wreak less havoc on infrastructure and homes than, say, fires in California, but they release incredible amounts of carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere.

That's because fires in the forests and tundra of the Arctic are typically left to burn unless they threaten cities or settlements. So they can wind up consuming hundreds of thousands of acres of vegetation. When the ground burns, carbon dioxide that was previously trapped in the Earth gets released into the air.

Data collected by the Copernicus program shows that fires in the Arctic in June released as much carbon dioxide in one month as the entire country of Sweden does in a year.

That influx of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere leads the planet to warm even more, which in turn increases the likelihood of similar Arctic fires in the future.

It's a perilous feedback loop.

"I sometimes hear 'there aren't that many people up there in the Arctic, so why can't we just let it burn, why does it matter?'" NASA researcher Liz Hoy said in a report. "But what happens in the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic - there are global connections to the changes taking place there."